Praveen Kumar urges athletes to bring A game in major events

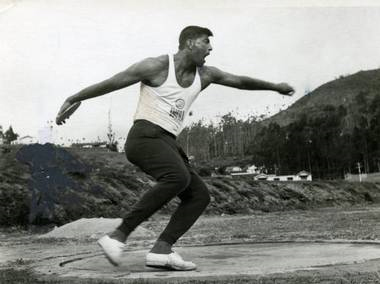

He has not fully recovered from a back surgery and spends much of his time in bed, but that has not stopped two-time Asian Games discus throw gold medalist, Praveen Kumar, from keeping track of developments in the society in general and athletics in particular. This Indian athletics Hall of Famer lights up each time he speaks about his sport and his own exploits.

“There would be nothing better than being able to watch an Indian on the Olympic Games podium, but it seems tough at the moment,” the gentle giant says. “I like how Neeraj Chopra, who I call a pocket transistor, has overcome his lack of height to throw the javelin great distances, but we have to be mindful of his competition,” he says, drawing attention to Johannes Vetter’s 97.76m throw.

Praveen Kumar, who will turn 73 in December, believes the outbreak of Covid-19 has been destructive for Indian athletes. “For them to return to their peak, they will need to compete in a number of events.

This break will have weakened many athletes. With the absence of competitions from their schedule, most will have been set back by a number of years,” he says.

He hasn’t forgotten either his rise from a humble family in Sarhali Kalan village, some 50km south of Amritsar, or any of his achievements in either discus throw or hammer throw during an international career that extended from 1966 to 1977 before he shifted attention to another aspect of entertainment, the world of films.

“I had just finished school examinations when I went to Kingston for the 1966 Commonwealth Games. We had reached a few days before my event. And when I wanted to go and practice, I was asked to take it easy. ‘Have we won medals at this level ever? Have fun and return home,’ I was told. I was determined to do well – and won a hammer throw silver there,” he recalls.

He speaks with the confidence of an athlete who took his A game in the big-ticket events as shown by a career-best hammer throw over 60.84m in the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City and a 53.12m discus throw in Munich four years later. “There is no other way to be. I had to be at the best possible at these events,” he says, wishing that facilities had been different in the 60s and 70s.

“I see how the Athletics Federation of India, under the leadership of (Dr. Lalit) Bhanot, has secured such wonderful training and competition opportunities for the athletes. I wish we had such backing in our times. I remember having to train for hammer throw with a chain that would be on the verge of breaking,” Praveen Kumar says.

“I am not exaggerating when I say that no one bothered about us. I did not even have a coach who could look at my technique. Each time I went to train in NIS, Patiala, my performance suffered. I used the services of my brother to analyse my throwing technique in my village until a coach from Los Angeles gave me a programme, asking me to concentrate on generating power,” he says.

Praveen Kumar recalls with fondness that none of his contemporaries had an ego problem. “There was a time when as a senior athlete I would go to meet newcomers in a camp to try and make them feel comfortable. We had wonderful camaraderie in the team and a great connect with the people who came to watch us compete,” he says. “We drew much from the recognition we got from them.”

He got nostalgic recalling the times trains were stopped en route by fans to be able to catch a glimpse of the stars of the time. “I wish our athletes become popular, not just on social media. Of course, they have to accept the popularity of cricket and football that is shown on television. I hope that we become a sports-playing nation rather than a sports-watching country,” he says.

Praveen Kumar also hoped that school principals are encouraged to enable a sports revolution. “I remember my school principal and teachers taking an interest in sports and encouraging us to play. We used to have three hockey teams in our school, but that pitch lies in state of repair now,” he says.

The bureaucrats appointed to the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports see their posting as a punishment. There can be no expectations from such officials. The sport is lucky that Bhanot has guided it the way he has, with passion and vision. Be it conducting international meets or ensuring that athletes trained methodically in extended national camps, he has been good for our sport.

I have given up hope that I would get the Padma Shri, but I do wonder how many Indian athletes have won two Asian Games gold medals, a silver each in an Asian Games and Commonwealth Games and a bronze in the Asian Games like I have. One of the more worrying things is how we have degraded our National Sports Awards, picking undeserving sportspersons for the honours.

“I hope the athletes will always put country ahead of all else. And if they have the fire within, they can take on the world,” Praveen Kumar says.